The Evolution of American Firearms (Late 18th–Mid 19th Century)

Back in the late 1700s through the mid-1800s, America was basically going through its “firearms glow-up” phase. Guns weren’t just clunky boomsticks anymore; they started getting serious upgrades. This was the time when breech-loading (loading from the back instead of shoving stuff down the barrel) and repeating mechanisms (shoot, reload faster, repeat!) showed up. Mass-produced muskets also became reliable enough to trust in battle.

But the real MVPs? Single-shot rifles.

These babies weren’t fancy repeaters, but they were simple, tough, and super accurate. Soldiers and settlers loved them because they could actually hit what they aimed at—whether that was in a war or while hunting dinner.

By 1838, a bunch of iconic rifles came out, each with its own quirks. Some were easier to reload, some shot straighter, but all of them shaped the future of firearms. They also had their headaches, slow reloading, heavy gear, and constant cleaning, but the lessons learned from these single shots paved the way for the modern rifles we know today.

So yeah, if you think of today’s rifles as sleek smartphones, these 1838 guns were like the brick-style Nokias—simple, strong, and built to last.

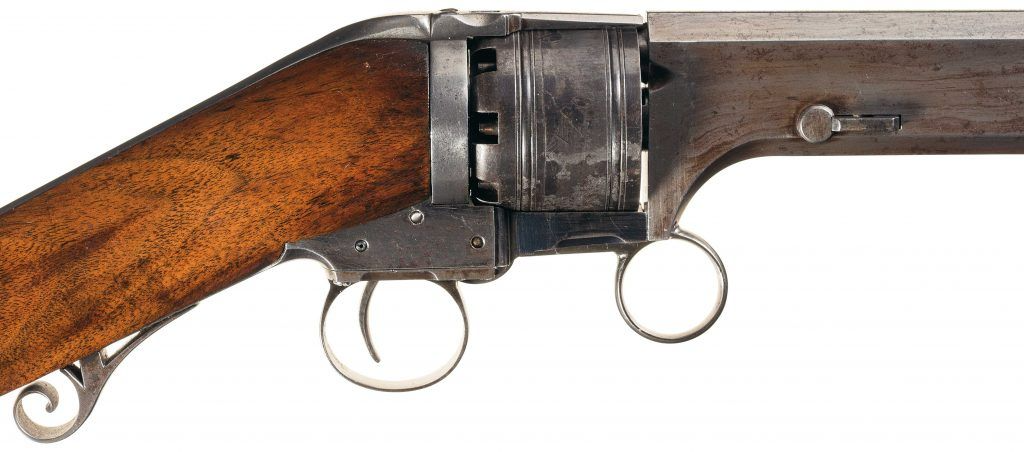

Colt Ring Lever Rifle (1837): Samuel Colt’s Early Revolving Rifle

Image Source-Pinterest

According to the YouTube video “Military-Issue Colt Model 1839 Paterson Revolving Rifle,” Colt’s first 1837 ring-lever rifle was fragile and underpowered. He improved it with the 1839 Paterson, a sturdier six-shot .525″ model, of which about 950 were made before his factory closed in 1842, with most sold to military buyers.

First Model (1837–1838): Features, Use, and Limitations

Features:

The Colt First Model Ring Lever Rifle was basically Colt’s first big “let’s make a rifle into a revolver” experiment. It had a long 32-inch octagonal barrel (fancy eight-sided style) with shiny brown-and-blue metal parts. The coolest part was the ring-shaped lever in front of the trigger—pulling it cocked the hammer and spun the 8-shot cylinder at the same time, like an old-school cheat code. It came in calibers from .34 to .44, so you could pick your “power level.” The walnut stock wasn’t plain either—it had a crescent-shaped buttplate, a cheek rest decorated with four carved horse heads, and the cylinder even had hunting scenes engraved on it. One unusual detail was the top strap over the cylinder, something Colt wouldn’t really bring back to 1873. Only about 200 of these rifles were ever made, making them super rare.

Usage:

Around 50 of these rifles were actually used by the U.S. Army in the Second Seminole War, and some were also handed out to the Texas Navy. Even though it wasn’t perfect, this rifle was a huge step in the early days of revolving rifle tech and showed Samuel Colt was onto something big.

Problems Faced:

For all its cool ideas, the rifle had some serious flaws. The ring lever system was complicated, broke down often, and wasn’t very reliable compared to later revolvers with simple external hammers. Soldiers found it tricky to use in real combat, and because of this, the design never caught on. In short: it looked awesome, but the mechanics were too messy for most people to trust.

Second Model (1838–1841): Refinements and Challenges

Image Source: Blue book of gun values

Features:

The second model maintained the core working principle but chose an open-top setup by eliminating the top strap. It was standardized in .44 caliber only. Barrel lengths were available in 28 inches or the more prevalent 32 inches. The cylinder displayed an engraving of a house scene rather than the previous hunting motif, and the inlaid cheekpiece was omitted. Enhancements included the integration of a loading lever, rounded edges on the rear of the cylinder, and a capping notch in the recoil shield. The standard cylinder held eight shots, though a small number of ten-shot variants were manufactured. In total, approximately 500 units were produced.

Usage:

This version experienced restricted application in both military and civilian settings. It continued to advance the development toward more practical revolving rifle designs.

Problems Faced:

Even with the modifications, the ring lever system stayed mechanically elaborate and vulnerable to operational failures. These persistent issues prevented it from gaining extensive popularity.

Hall Model 1819 Rifle: America’s First Breech-Loading Military Rifle

Image Source-AI

In this YouTube video, “Hall Model 1819: A Rifle to Change the Industrial World,” John Hall is shown to have created the first U.S. military breechloading rifle, adopted in 1819. More importantly, at Harpers Ferry Arsenal, he invented interchangeable manufacturing, a breakthrough that shaped modern industry.

Features:

Manufactured from the 1820s through the 1840s, the Hall Model 1819 introduced a groundbreaking breech-loading mechanism. The chamber formed a detachable rear section of the barrel that could pivot upward, enabling rapid insertion of powder and projectile without the need to ram them the entire barrel length. This setup allowed for rifled barrels paired with snugly fitted projectiles. Consequently, it enhanced both the speed of loading and the precision offered by rifling.

Usage:

Adopted by American infantry units, the Hall rifle signified a major technological leap in firearms. It provided superior firing rates and improved accuracy over traditional smoothbore muskets.

Problems Faced:

Fouling from black powder continued to impede sustained rapid fire and necessitated regular cleaning. The breech system suffered from problems related to sealing and long-term durability. Furthermore, its intricate mechanics demanded more intensive maintenance than basic muzzle-loading weapons.

American Long Rifle (1792 Contract Rifle)

Image Source: International Military Antique

Features:

The 1792 Contract Rifle operated as a muzzle-loading flintlock with a 42-inch octagonal barrel in .49 caliber. Primarily crafted by Pennsylvania gunsmiths under federal contracts, it followed conventional loading methods: powder was poured into the barrel, followed by a patched ball, and ignition occurred via the flintlock. The stock incorporated a patch box for storage. Variants with shorter barrels, ranging from 33 to 36 inches, were employed during the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Usage:

This rifle saw extensive service in early U.S. conflicts such as the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War. Its design inspired subsequent compact “plains rifles” like the Hawken, which were preferred by mountain men and fur trappers for their ease of transport and suitability for mounted use.

Problems Faced:

The extended barrel reduced overall portability in various scenarios. Reloading became sluggish and cumbersome once fouling accumulated in the barrel. The absence of uniform parts also posed challenges for repairs and logistical support.

U.S. Model 1835 Musket: Standard Infantry Firearm of Its Time

Features:

The U.S. Model 1835 Musket was a .69 caliber flintlock firearm with a 42-inch smoothbore barrel and an overall length of 58 inches. It weighed approximately 10 pounds and utilized paper cartridges containing either buck and ball or an undersized .65 caliber musket ball to mitigate powder fouling. The muzzle-loading design allowed for a firing rate of two to three rounds per minute under typical conditions. Muzzle velocity ranged from 1,000 to 1,200 feet per second, with sights consisting of a front sight integrated into the upper barrel band. Many examples were later converted to percussion lock systems, and some had their barrels rifled if structurally suitable.

Usage:

Produced from 1835 to 1840 at the Springfield Armory, Harpers Ferry Armory, and by private contractors, this musket served the United States military from 1835 to 1865. It was employed by both Union and Confederate forces during the American Indian Wars, the Mexican-American War, and the American Civil War. The design emphasized interchangeable parts, building on earlier models like the Springfield Model 1816 Type III, and represented a standard infantry weapon in mid-19th-century conflicts.

Problems Faced:

The flintlock mechanism was prone to misfires in adverse weather conditions and required frequent maintenance to address fouling from black powder residue. Conversions to percussion were common due to the flintlock’s unreliability, and not all barrels could be rifled owing to variations in thickness that affected structural integrity. The effective firing range was often limited to 50 to 75 yards in practice, falling short of the theoretical 100 to 200 yards.

U.S. Model 1840 Musket: The Last Flintlock in U.S. Military Service

Image Source-Pinterest

Features:

The U.S. Model 1840 Musket featured a .69 caliber flintlock with a 42-inch smoothbore barrel and an overall length of 58 inches. Weighing about 9.8 pounds, it included a heavier barrel design compared to its predecessor to facilitate potential rifling, along with a stock incorporating a comb and a longer bayonet equipped with a clasp. It was muzzle-loaded using paper cartridges with buck and ball or an undersized .65 caliber musket ball to reduce fouling effects. The firing rate was two to three rounds per minute, with muzzle velocity between 1,000 and 1,200 feet per second. Sights comprised a front sight cast into the upper barrel band, and rear sights were added during later conversions.

Usage:

Manufactured from 1840 to 1846 at the Springfield Armory, Harpers Ferry Armory, and by contractors such as D. Nippes and L. Pomeroy, approximately 30,000 units were produced. This musket remained in service from 1840 to 1865 and was used by United States and Confederate forces in the American Indian Wars, the Mexican-American War, and the American Civil War. It marked the final flintlock musket adopted by the U.S. military, with many units converted to percussion and rifled before or during active deployment.

Problems Faced:

As with other flintlock designs, it suffered from vulnerability to weather-related misfires and black powder fouling that could impede reloading and accuracy. The actual effective range was typically 50 to 75 yards, less than the stated 100 to 200 yards, highlighting limitations in practical combat performance. While the heavier barrel addressed some structural concerns for rifling, the need for widespread conversions to percussion indicated ongoing reliability issues with the original mechanism.

Key Challenges in Early American Rifle Development

Early American rifle development faced significant obstacles that shaped the trajectory of firearms innovation:

- Mechanical Complexity: The Colt Ring Lever Rifles’ revolving cylinder and ring lever system, while innovative, were prone to mechanical failures, limiting reliability and adoption.

- Breech-Loading Limitations: The Hall Model 1819’s breech-loading mechanism improved loading speed and accuracy but struggled with fouling, sealing issues, and durability, requiring frequent maintenance.

- Flintlock Reliability: The U.S. Model 1835 and 1840 muskets, designed for mass production, suffered from weather-sensitive flintlock ignition and fouling, restricting their effectiveness in combat.

- Portability and Standardization: The American Long Rifle’s long barrel hindered portability, and the lack of interchangeable parts complicated repairs, particularly in military contexts.

These challenges underscored the need to balance innovation with practicality, driving advancements toward percussion and cartridge-based systems in later decades.

Legacy of Single-Shot Rifles in American Firearms History

Single-shot rifles laid the groundwork for modern firearm technology, serving as reliable tools for hunting, defense, and warfare. Their evolution from muzzle-loading flintlocks to breech-loading designs in the 19th century improved loading speed and accuracy while maintaining mechanical simplicity. Notable examples, such as the Springfield Model 1873 “trapdoor” rifle and the Winchester Model 1885, demonstrated the durability and precision of break-action mechanisms, favored by hunters and marksmen. Although repeating rifles and bolt-action designs eventually surpassed them, single-shot rifles remained valued for their accuracy, ease of maintenance, and suitability for target shooting and big game hunting into the 20th century. Their influence shaped firearm manufacturing, particularly in the development of strong, accurate barrels and reliable actions, informing the design of subsequent military and sporting rifles.

Conclusion

The single-shot rifles of 1838, including the Colt Ring Lever Rifle, Hall Model 1819, American Long Rifle, and U.S. Model 1835 and 1840 muskets, exemplified the transitional nature of American firearms development. These weapons introduced innovative mechanisms like revolving cylinders and breech-loading systems while addressing the practical demands of reliability and mass production. Despite challenges such as mechanical complexity, fouling, and weather sensitivity, their contributions established critical foundations for the evolution of modern firearms, influencing both military tactics and civilian applications for generations.